Treating “Climber’s Elbow” (Medial Epicondylitis)

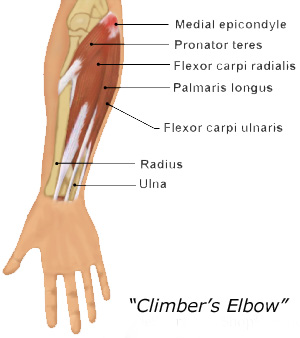

Pain near the medial epicondyle is commonly called “golfer’s elbow” or climber’s elbow. Pain develops in the tendons connecting the pronator teres muscle and/or the many forearm flexor muscles (responsible for finger flexion) to the knobby, medial epicondyle of the inside elbow.

In many cases, medial tendinosis is a gradual-onset overuse injury due to climbing too often, too hard, and, most important, with too little rest. Furthermore, developing forearm muscle imbalance and muscle adhesions (trigger points) often contribute to elbow pain and exacerbate the injury. It’s also important to note that there are a number of less common injuries that can cause elbow pain and mimic climber’s elbow. If your elbow pain is significant and/or getting worse, I strongly recommend visiting a doctor versed in climbing injuries.

Anatomy Overview

Anatomy Overview

Consider that all the muscles that produce finger flexion are anchored on or near the medial epicondyle. Furthermore, the muscles that produce hand pronation (that turn the palm outward to face the rock) originate from the medial epicondyle. Biceps contraction produces supination (turning of the palm upward), but in gripping the rock you generally need to maintain a pronated, palms-out position. This battle, between the supinating action of the biceps pulling and the necessity to maintain a pronated hand position (to maintain grip with the rock), strains the pronator teres muscle and its attachment at the medial epicondyle.

Given the above factors, it’s easy to see why the tendons attaching to the medial epicondyle are subjected to sustained stress and, inevitably, develop microtraumas. Just as muscular microtraumas are repaired to new level of capability, the tendons increase in strength and can withstand higher stress loads given adequate rest. Unfortunately, the repair and strengthening process occurs more slowly in tendons than in muscles. Eventually, the muscles are able to create more force than the tendons can adapt to—the result is injury.

Tendinosis will reveal itself gradually through increasing incidence of painful twinges or soreness during or after climbing. Tendinitis, however, is evidenced by acute onset of pain in the midst of a single hard move (or failed move), and is usually followed by inflammation and palpable swelling. Even in these cases cumulative microtrauma may be involved in making the tissue vulnerable to acute trauma.

Treatment and Rehab

With climber’s elbow, as in treating other injuries, you can more easily manage tendinopathy (any tendon injury) and speed your return to climbing by early recognition of the symptoms and proactive treatment. The mature and prudent approach of attending to the injury early-on versus trying to “climbing through it” could mean the difference between six weeks and six months (or more) of climbing downtime.

Treatment of tendinosis and tendinitis has two phases: Phase I involves steps to relieve pain and reduce inflammation (in the case of tendinitis); Phase II is engaging in rehabilitative and stretching exercises to promote correct alignment of collagen tissue and prevent recurrence.

Phase I demands withdrawal from climbing (and all sport-specific training) and commencement of pain-reducing and anti-inflammatory measures. Icing the elbow for twenty minutes, three to six times a day, and use of NSAIDs will help reduce inflammation and pain following injury; cease use within a few days to a week. A cortisone injection may be helpful in chronic or severe cases, though this practice is somewhat controversial among physicians and, in fact, may be detrimental to the healing process. Depending on the severity of the injury, successful completion of Phase I could require anywhere from two weeks to a month or two months.

The goal of Phase II is to retrain and rehabilitate the injured tissues through use of mild stretching and strength-training exercises. Since forearm-muscle imbalance plays a primary role in many elbow injuries, it’s vital to perform exercises that strengthen the weaker aspects of the forearm—hand pronation for medial tendinosis and hand/wrist extension for lateral tendinosis (pain near the outside/lateral boney aspect of the elbow, and the topic of a separate article).

Although some dull pain is likely during this rehab phase, avoid any exercise or activity that causes sharper pain or lingering (or worsening pain) after a workout. Pull-ups, fingerboarding, and campus training are often problematic and should only be done in small doses, if at all, until the condition has resolved.

Always perform some general warm-up activity and consider warming the elbow directly with a heating pad before beginning the stretching and strengthening exercises. Stretch twice daily the forearm flexor, extensor, and pronator muscles (see below). Once the stretching exercises have successfully restored normal range of motion with no pain, you can introduce strength training with the forearm pronator exercise (below). It’s important to progress slowly with training exercises and to cut back at the first sign of anything more than slight pain. Begin with just a couple of pounds of resistance and gradually increase the weight over the course of a few weeks. Use the stretching exercises daily, but do the weight-training exercises only three days per week.

After three to four weeks of rehab/training, begin a gradual return to climbing. Start with easy vertical routes, and take a month or two to return to your original level of climbing. Continue with the stretching and strength-training exercises indefinitely—as long as you are a climber, you must engage in these preventive measures. Failed rehabilitation and relapse into chronic pain may eventually lead to a need for surgical intervention.

Extensors Stretch

Stretches & Exercises

This important stretch targets the numerous extensor muscles of the lateral forearm as well as the brachioradialis muscle. These muscles are especially strained when crimping with a chicken-winged arm position, and so daily stretching (and use of an Armaid, if you own one) is essential for lengthening the tissues and releasing tension that can eventually contribute to lateral epicondylitis.

With nearly straight arms, cross your hands in front of your body and interlace your fingers, palms together. While maintaining mild tension throughout the length of both arms, pull with one hand to flex the wrist of the other hand until you feel the stretch develop in the finger/wrist extensors along the outside of the forearm. Hold the stretch for about twenty seconds and then pull with the other hand to create a stretch along the other arm. Perform the stretch twice on each arm. This is a good stretch to do every day, whether you’re at work, home, then gym, or the crags. Just do it!

In a standing position, bring your arms together in front of your waist. Straighten the arm to be stretched and lay the fingertips into the palm of your other hand. Position the hand of your stretch arm so that the palm is facing down with the thumb pointing inward. Pull back on the fingers of your straight arm until a mild stretch begins in the forearm muscles. Hold this stretch for about twenty seconds. Release the stretch and turn the hand 180 degrees so that your stretch arm is now positioned with the palm facing outward and the thumb pointing out to the side. Using your other hand, pull your fingers back until a stretch begins in the forearm muscles. Hold for ten seconds. Repeat this stretch, in both positions, with your other arm. Finish up with a minute of self-massage to the forearm flexor muscles using deep cross-fiber friction.

The exercise targets the small pronator teres muscle that often contributes to elbow pain and some cases of tendinosis. Sit on a chair or bench with your forearm resting on your thigh with the hand in the palms-up position. Firmly grip a sledgehammer with the heavy end extending to the side and the handle parallel to the floor. Turn your hand inward (pronation) to lift the hammer to the vertical position. Stop here. Now, slowly lower the hammer back to the starting position–slowly count to five as you perform the lowering (eccentric) phase. Stop at the horizontal position for one second before beginning the next repetition. Continue lifting the hammer in this way for fifteen to twenty repetitions. Choke up/down on the hammer to adjust the resistance/difficult. Perform two sets with each hand. Note: When used as a rehab exercise, it’s best to do only the lowering phase–use your free hand to assist in returning the hammer to the top position.

Summary Tips for Treating Elbow Tendinosis

- Cease climbing and climbing-specific training.

- Apply ice to the injured area and take NSAID medications only if the injury produces palpable swelling (most elbow tendinopathy does not) or persistent pain. Cease use of ice and NSAIDs as soon as swelling and pain diminish—further use may slow healing.

- Never use NSAIDs to mask pain in order to continue climbing while injured. Regular use of NSAIDS (and smoking) may actually weaken tendons!

- If no swelling is present, begin mild stretching, light massage, and use of a heating pad. Do this for ten to fifteen minutes, three times per day. Most important is twice-daily use of the forearm stretches shown above.

- Use an Armaid daily to improve forearm muscle tissue quality (never use on tendons).

- If no swelling is present and if pain is minor, engage in rehabilitative exercises on an every-other-day basis. Perform some warm-up activities such as arm circles, finger flexions, massage, or use of a heating pad. Use reverse wrist curls and reverse arm curls for lateral tendinosis and forearm pronators for medial tendinosis.

- Cautiously return to climbing when your elbow is pain-free and no sooner than after two to four weeks of strength-training exercise. Begin with easy, foot-oriented climbing for the first few weeks, and limit use of the crimp grip. Cease climbing if you experience pain while climbing and immediately return to step 2.

- Commit to long-term training of the forearm pronator and extensor muscles. Perform daily stretching and Armaid use for as long as you are an active climber.

- Consider consuming the research-based supplement Supercharged Collagen to support collagen synthesis and strengthening of sinew.

Copyright © 2019 Eric J. Hörst